Caspian Terns

The Rapid Growth and Decline of the Caspian Tern Colony on the Copper River Delta

By Teal Barmore, March 12, 2019

The discovery of a Caspian Tern colony on one of the barrier islands of the Copper River Delta in 2005 by Tyee and Teal Lohse was no surprise to Prince William Sound Science Center researcher Dr. Mary Anne Bishop. Sightings of Caspian Terns and their young had been regularly reported since the late 1980s, and in many ways, the barrier island that they settled on is the perfect habitat for a breeding colony. It’s a federally owned sandy island, mostly devoid of potential mammalian predators, with very few nesting gulls who would try to steal their eggs. The remote location makes the island relatively safe from human disturbance and development as well. Unfortunately, like many of the world’s coastal communities and colonies, the Caspian Tern colony is not safe from the effects of climate change. Nine years of colony monitoring shows what the future might look like for these resilient birds.

Mary Anne first started monitoring the Copper River Delta colony in 2008. A Caspian Tern habitat management program in Oregon had been initiated with the intent of dispersing thousands of breeding pairs of Caspian Terns from East Sand Island where they were preying on already pressured juvenile salmon in the Columbia River Estuary. Oregon State University researchers color-banded birds from East Sand Island as well as at other breeding colonies on the west coast to learn more about colony connectivity. They predicted that the displacement of Caspian Terns in Oregon would increase the populations of breeding colonies elsewhere, including as far away as the Copper River Delta. For the next nine years, Mary Anne Bishop and Oregon State University researchers worked together to monitor the Copper River Delta colony. In addition to watching for color bands from East Sand Island, they surveyed the colony’s size, location, and habitat. They counted active nests and banded birds from the Copper River Delta colony with their own color bands for four of the survey years.

Dr. Mary Anne Bishop works together with Oregon State researcher Yasuko Suzuki to band Caspian Terns on the Copper River Delta in 2009.

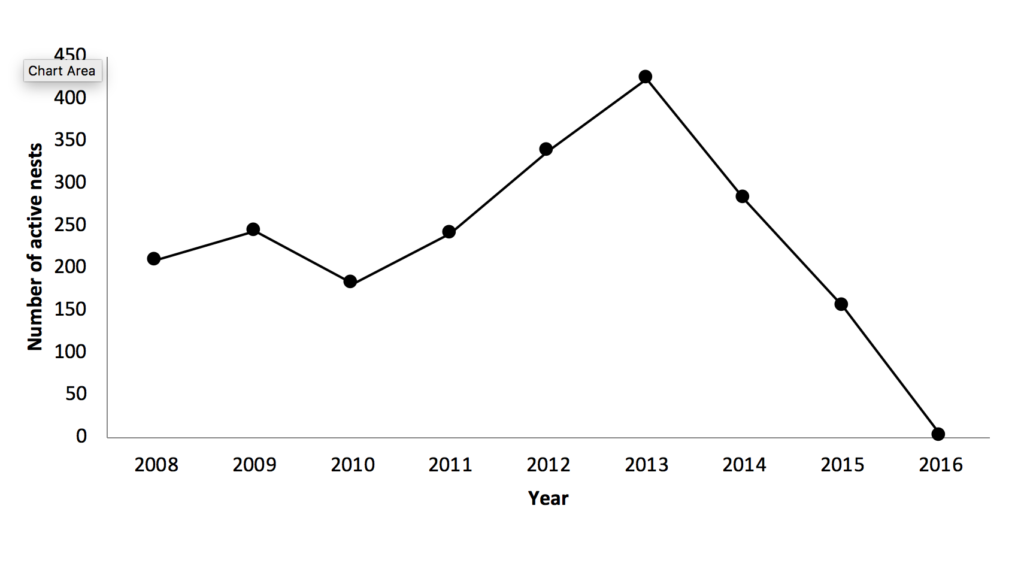

What they found verified their prediction. From 2008 to 2013 the colony more than doubled in size, and several birds banded on East Sand Island were re-sighted at the Copper River Delta colony. A few East Sand Island birds were first observed at a colony in Icy Bay, southeast of the Copper River, and then again at the Copper River a year or two later, suggesting their incremental movement to the north. They also saw birds from other places in the Copper River Delta colony. One bird, in particular, received a lot of attention. It was banded as a breeder in San Francisco. One year it was observed early in the breeding season in San Francisco, then it showed up in the Copper River Delta colony in the same breeding season, and it was on a nest! The Caspian Terns were dramatically expanding their range.

What they also saw in the Copper River Delta colony were the effects of climate change. The first downturn for the colony was observed in 2010. When the researchers visited the island that spring, they observed that high water from storm surges had been right up to the edge of the nesting colony. It coincided with the first year that there was a decline in the population suggesting that nests had been washed away in the flooding. Flooding events were also observed in 2012, 2014, and 2015. By 2012 though, some of the birds had caught on and had started to nest in the higher dunes on the island.

What the Caspian Terns had learned from increased storm surges couldn’t help them when it came to the effects of the marine heatwave that started in the fall of 2013 and lasted through 2016. The breeding population rapidly fell and by 2016 there was literally only one nesting pair at the site. “It was so sad,” Mary Anne recalls. “There were birds hanging around. When we walked up in the morning there were 50 birds, but no nests.” That same year, there were thousands of gulls in town signifying that the gulls were also struggling to breed. Mary Anne suspects that the birds just didn’t have food. The forage fish populations that usually sustain them appeared to have been dramatically impacted by the persistent warm marine waters.

The future of the Copper River Delta Caspian Tern colony is uncertain. As recently as 2018 the colony appeared to have been affected by flooding. And since fall 2018, warm sea surface temperature anomalies suggest that we’re experiencing another marine heatwave. It will be interesting to see if there is a breeding colony on the Delta at all this spring. If not, they will have moved somewhere else. Maybe to another barrier island that is less susceptible to flooding, or over by Cook Inlet where they have been reported. Maybe they will continue their spread to the north and west, joining smaller colonies on to the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, or go all the way to the Arctic where one breeding pair was observed in 2016.

Results mentioned in this article were published in March 2019 in the scientific journal Waterbirds in a paper titled “Colony Connectivity and the Rapid Growth of a Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia) Colony on Alaska’s Copper River Delta, USA.”