Status of PWS Herring

Aerial herring surveys show record low biomass

By Teal Barmore, January 14, 2019

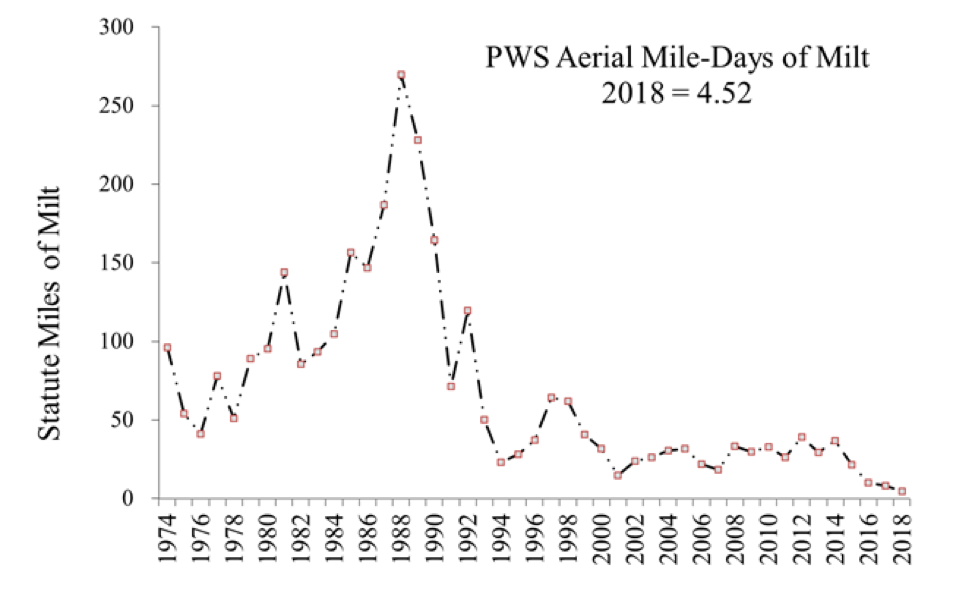

In April 2018 when researchers from the Herring Research and Monitoring program set out into Prince William Sound for the annual Pacific herring surveys, they did not think the population could get any lower than the previous year’s record of about 9,000 tons. Results from 40 hours of aerial surveys and the Prince William Sound Science Center’s acoustic biomass surveys proved otherwise. The Prince William Sound Pacific herring population has dropped to a record low of around 3,000 to 4,000 tons. Considering that the population was fairly consistently around 20,000 tons only four years ago and was once in the 120,000-ton range, this brings about questions of why this population is struggling and how its low numbers are reflected throughout the food chain.

Fortunately, the Herring Research and Monitoring program has been exploring these very questions for the last six years. Program manager, Scott Pegau, has reasons to believe that a combination of disease and warmer ocean conditions leading to poor body conditions are among the culprits.

The recent low numbers first started in 2015. Researchers anticipated a big year class of herring coming in but what they found instead was a declining population. A spike in the percentage of fish with antibodies for the deadly virus hemorrhagic septicemia indicated that a disease outbreak may have been responsible for the poor recruitment.

Hemorrhagic septicemia causes hemorrhages that kill fish very fast. Once an outbreak starts, the fish start generating huge amounts of the virus allowing it to sweep through a population rapidly. It tends to be more lethal in colder temperatures leaving only 10 to 20 percent of the population alive. For every thousand tons of fish that have virus resistant antibodies somewhere between six and eight thousand that don’t would be expected to die in a winter outbreak.

From 2014 to 2015 the herring population dropped from about 20,000 tons to 10,000 tons and the percentage of fish with antibodies jumped from a fairly normal percentage of around 8% to over 25%. In the following years the percentage of antibodies returned to normal, but the population remains low, and herring aren’t the only one’s suffering. Seabird nests have failed for several years and whales have been skinny. Scott notes that other forage fish may have also been affected. We happen to be watching herring closely, but the results are ecosystem wide.

Poor body condition of herring in recent years leads Scott to believe that the warm ocean conditions and the resulting lack of herring’s usual food source could be to blame. Prince William Sound herring get their energy from zooplankton and when water temperatures are normal herring can find energy rich copepods with a lot of lipids and fats. Warmer waters tend to favor smaller copepods that don’t have the fat.

In one regard, at least, things are looking up for the herring. In 2018 there was a slight increase in the weight and length of sampled herring, indicating that ocean conditions have become a little more favorable for them. Scott is hopeful that this will allow the population to recover.