Hydroacoustic Spawning Biomass Surveys

Hydroacoustic spawning biomass surveys of Pacific herring

By Teal Barmore, March 23, 2020

Every spring, researchers from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) and the Prince William Sound Science Center (PWSSC) work together to estimate the spawning biomass of Pacific herring in Prince William Sound (PWS). This project is part of a greater effort by the Herring Research and Monitoring program to track the recovery of herring since its decline in 1993. Spawning biomass, the mass of the entire spawning population, is calculated using two methods in PWS. The original method of aerial surveys was improved upon when PWSSC researcher Jay Kirsch, along with John Wilcock, Gary Thomas, and Kevin Stokesbury came up with the hydroacoustic survey method in the early 1990s. Dick Thorne carried on the program for many years until Dr. Pete Rand took over. Since then, the program has used both methods: aerial surveys for their ability to cover a lot of ground and acoustic surveys to look deeper. The results tend to reinforce each other.

Predators such as whales and sea lions are indicators that herring might be in an area. Photo by David Janka of Auklet Charters.

Acoustic surveys, headed up by PWSSC research ecologist Pete Rand, are usually done in two parts: first in the eastern sound including Ports Gravina and Fidalgo, and later in the western sound near Montague Island. About three or four nights of surveying are done in each region.

On a typical cruise, researchers spend the day looking for signs of herring in the area. At 30 to 40 meters deep, it’s not easy to see a school of herring from a boat, so predatory activity is the best indicator. Whales, sea lions, diving birds, gulls, and eagles all turn out for the feast when herring are around.

Once the researchers have found fish, they wait until nightfall to do the acoustic survey. At night, herring tend to rise off the bottom and spread out, allowing more accurate readings from the acoustic survey technology. Around 11:00 p.m. the researchers, working under red-filtered lights (deck lights are turned off for stealth), lower a transducer connected to an aluminum tow-fin into the water alongside the boat. This transducer works much like a fish finder or sonar on a boat, sending sonar wave (sound wave) “pings” down into the water. When the wave hits something and bounces back it contains information on the size and depth of the object it hit. Once an echo is received at the transducer, a digital signal is passed through the cable to an on-board computer where the data is saved. An echogram display on the computer allows the researchers to observe patterns in herring schools as the vessel makes its way through the transects.

The aluminum tow-fin in the water for a test run during the day. Photo by Pete Rand.

“Herring tend to aggregate in large schools at about 40 meters, initially staying deep, probably to avoid surface predators. At some point they tend to move to shallower water and spawn over “structure” (typically kelp beds)—eggs stick to them.” –Pete Rand

The sonar that Pete uses is a scientific echosounder that has a narrow beam and high sensitivity. The system is carefully calibrated on each cruise, so the resulting data is collected consistently every year. With the transducer in the water, the researchers begin slow zig-zag transects in the area where they suspect the fish are aggregating.

Surveys typically last four to five hours, enough time to cover the entire aggregation area, which is often well defined by the patterns that researchers see on the echogram, and the spatial patterns of the predators that were observed the day prior to the survey.

The downside of using acoustic survey to estimate biomass is that it doesn’t tell you for certain what species of fish you are picking up. Pete usually has a good idea based on the shape of the school and the location of the fish. But to double check, ADF&G does “ground-truthing” by catching a very small sample of the fish for identification. Each fish is identified by species and later measured for length, identified as male or female, and aged by markings in their scales that are similar to tree rings.

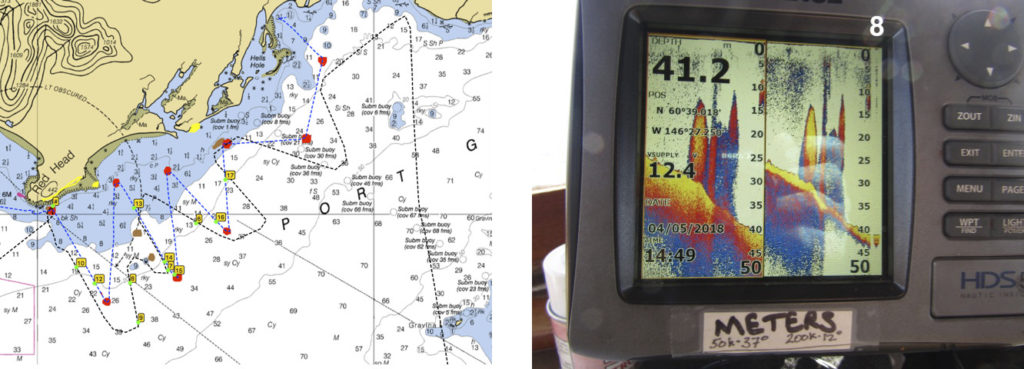

Track lines for the night transect on April 5. The schools of herring on the depth sounder (sonar) correspond with the marker on the chart. Photos by David Janka of Auklet Charters.

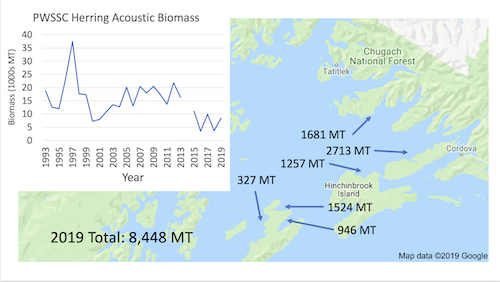

The main goal of the acoustic monitoring project is to find out how many thousands of metric tons of herring are in the sound for ADF&G’s stock assessment models, but the data is also used to look at distribution changes. “There has been a shift,” Pete observed. “There used to be a lot more fish in the western part of the sound, now most of them are spawning in the eastern part of the sound. Sometimes there are herring spread across several bays, but in recent years we’re only finding fish in Gravina.” Over the years since the project started, the time series has shown that there were a lot more fish in the late 1990s and it has been going down in recent years. The 2018 survey results showed the lowest recorded biomass. Poor body conditions in previous years led Herring Research and Monitoring program manager Scott Pegau to believe that warm ocean conditions and the resulting lack of lipid-rich plankton could be a big part of the problem. The 2018 herring did have improved body conditions over fish sampled in previous years, correlating with a return to cooler ocean temperatures during the summer months when herring fatten up on abundant plankton. Hope was further renewed in 2019 when a relatively large group of three-year-old herring joined the spawning population. Though the good recruit year nearly tripled the population it is still very low. Scott holds out hope though; herring can build a very large population from a small one depending on how many youngsters join the spawning stocks in a given year. The population may be beginning to build again.

The time series since acoustic biomass surveys started in 1993. When compared with other populations around the world, the collapse of herring in PWS is unusual in how low the population reached and the duration of the crash.

It is important to keep in mind this is one of the many research projects in the Herring Research and Monitoring Program. Along with the abundance monitoring (both acoustic and aerial surveys) there are ongoing projects examining the role of disease and infection on herring survival, determining at what age herring first start spawning and developing better assessment models to describe the trends we are observing. We still struggle with explaining exactly why the herring declined in the first place and what is preventing their recovery in Prince William Sound. Answers don’t come easy, and as Pete points out, “These fish are obviously coping with a lot in the Sound, including a marine heat wave, predators, and finding food. They do seem to be between a rock and a hard place. Being out on the water and collecting data like we do every spring definitely helps us work toward some answers.”

Editors note: This post was originally published in April of 2018 but has been updated to reflect the current state of knowledge as of March 2020.