Marine Heat Wave Update

Marine Temperatures Anomalies Doubled Previous Records

By Teal Barmore, October 24, 2019

A mild winter followed by an abnormally calm and sunny summer this year led to marine water temperatures that doubled the previous marine heatwave record in Prince William Sound. Science Center oceanographer Dr. Rob Campbell observed that monthly average temperatures at the surface during the months of July and August were seven degrees Fahrenheit above the seasonal average with one observation of nine degrees above average.

Temperatures are recorded by Rob for his work with the Gulf Watch Alaska program. In addition to routine measurement of various oceanographic parameters at 12 different locations in the Sound, Rob maintains the Prince William Sound Autonomous Profiler (PAMPR). The PAMPR journeys from a depth of 60 meters to the surface twice a day measuring temperature, salinity, oxygen concentrations, chlorophyll-a concentrations, turbidity, and nitrate concentrations. A recently added plankton camera goes along for the ride as well.

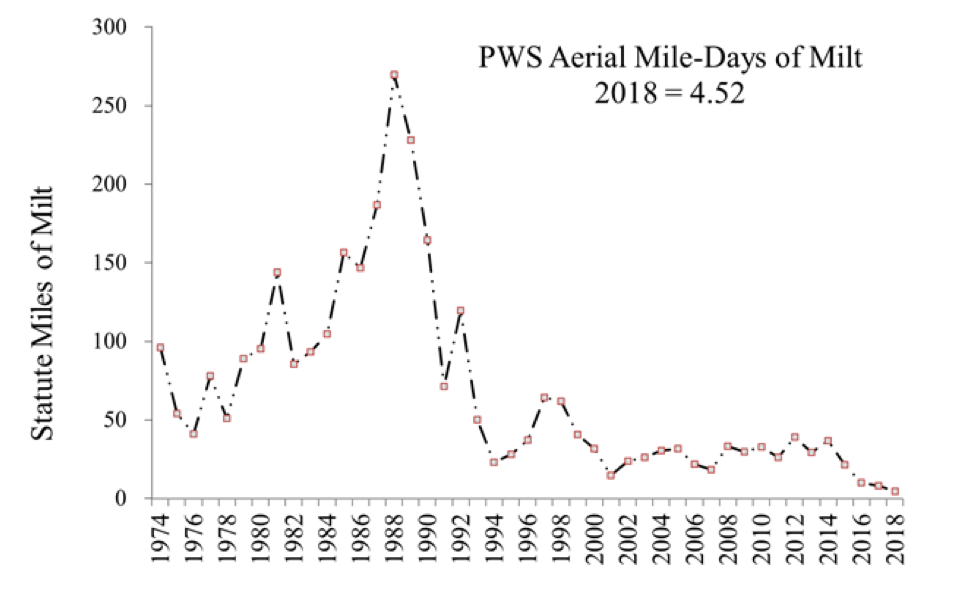

Rob compares the temperature data from the PAMPR to chlorophyll-a and nitrate concentrations to observe how phytoplankton, the base of the marine food chain, are reacting to these environmental changes. It appears that they haven’t been doing great. For the last two decades the overall productivity of the spring plankton bloom in Prince William Sound has been declining. Rob thinks that this is probably due to limited nutrients in a changing surface layer.

Every year, waters in the subarctic go through a cycle. Winter wind and wave action mixes cold nutrient rich waters from the depths up to the surface. By spring, the combination of these nutritious rich waters and increasing sunlight at the surface are ideal for a big plankton bloom. As the spring sun shines on the water, and less dense fresh water from melting glaciers flow into the ocean, a strong surface layer forms where the plankton bloom is ‘pinched off’. Until the next fall and winter storm cycles there isn’t much transfer between that warm top layer and the cold nutrient rich water below. The nutrients that are there are all the plankton get.

Rob thinks that the declining trend in productivity might have to do with a change in the depth of that warm surface layer. He estimates that the surface layer was historically closer to 40 or 50 meters in depth, giving the plankton a lot more nutritious water to grow in. In recent years the layer has been more like 10 or 20 meters deep.

Temperature anomalies as seen by the PAMPR in central Prince William Sound this summer. The cold anomaly below the hot surface layer during the summer is likely an indication that the surface layer is thinner than average.

Low phytoplankton productivity can be expected to work its way up the food chain, and Rob is keeping an eye on the next level too – zooplankton. After the marine heat wave known as the ‘blob’ from 2014-2016, Rob saw an interesting shift in the zooplankton of Prince William Sound. Starting in 2015, there were more warm-water species of zooplankton than average, even with low phytoplankton concentrations. Warm-water zooplankton species that are more typically found in Oregon and Washington are generally smaller and need less food so it makes sense that their numbers would be high despite low phytoplankton productivity.

What happens with the layer of exceptionally warm water in Prince William Sound next, depends on what kind of winter we have. According to Rob, we need our normal raging North Pacific storms to mix everything up. A mild winter could lead to another persistent marine heat wave.

Feature photo courtesy of NOAA/NESDIS.